Campus Conservatives See Resurgence in the Aftermath of Charlie Kirk

The right-wing campus group Young Americans for Freedom has a long history, and their prominence appears to be on the rise.

This story was originally written for Gay Times Magazine. Keywords: Young American Foundation, anti trans, trump transgender, hate speech, lgbtq hate, is hate speech protected, right wing news outlets, right to assemble, most conservative colleges, Charlie Kirk assassination

It was a quiet Thursday ahead of Thanksgiving break at the University at Buffalo (UB) when Maria B. Quagliana received an email from the school that said campus police had confiscated several firearms from a student in response to reports of a “concerning conversation.”

That student was Jacob Cassidy, the president of UB’s chapter of Young Americans for Freedom (YAF), a right-wing student group. Cassidy had been overheard threatening to shoot up the school, allegedly telling his friend that he had “a foldable AR in [his] bag,” adding: “I’ll shoot them in the foot and knee so they can’t get away.”

Quagliana, a first-year student at UB’s law school, had run into Cassidy a week earlier at a counter-protest of a YAF event in support of ICE deportations. While Cassidy has received an interim suspension, Quagliana has still felt “extremely anxious” since getting the alert.

“This person knows what I look like,” Quagliana told Uncloseted Media and GAY TIMES. “I’ve had multiple panic attacks either in my car or waiting to walk into the building.”

Quagliana says that this was just the latest in a string of incidents surrounding YAF on campus. The group, which was prominent in the 1960s but faded into the background over time, has experienced a resurgence in activity nationwide and now reportedly has over 400 chapters at colleges and high schools in the U.S. That resurgence comes in the wake of the assassination of conservative campus activist and co-founder of Turning Point USA (TPUSA) Charlie Kirk.

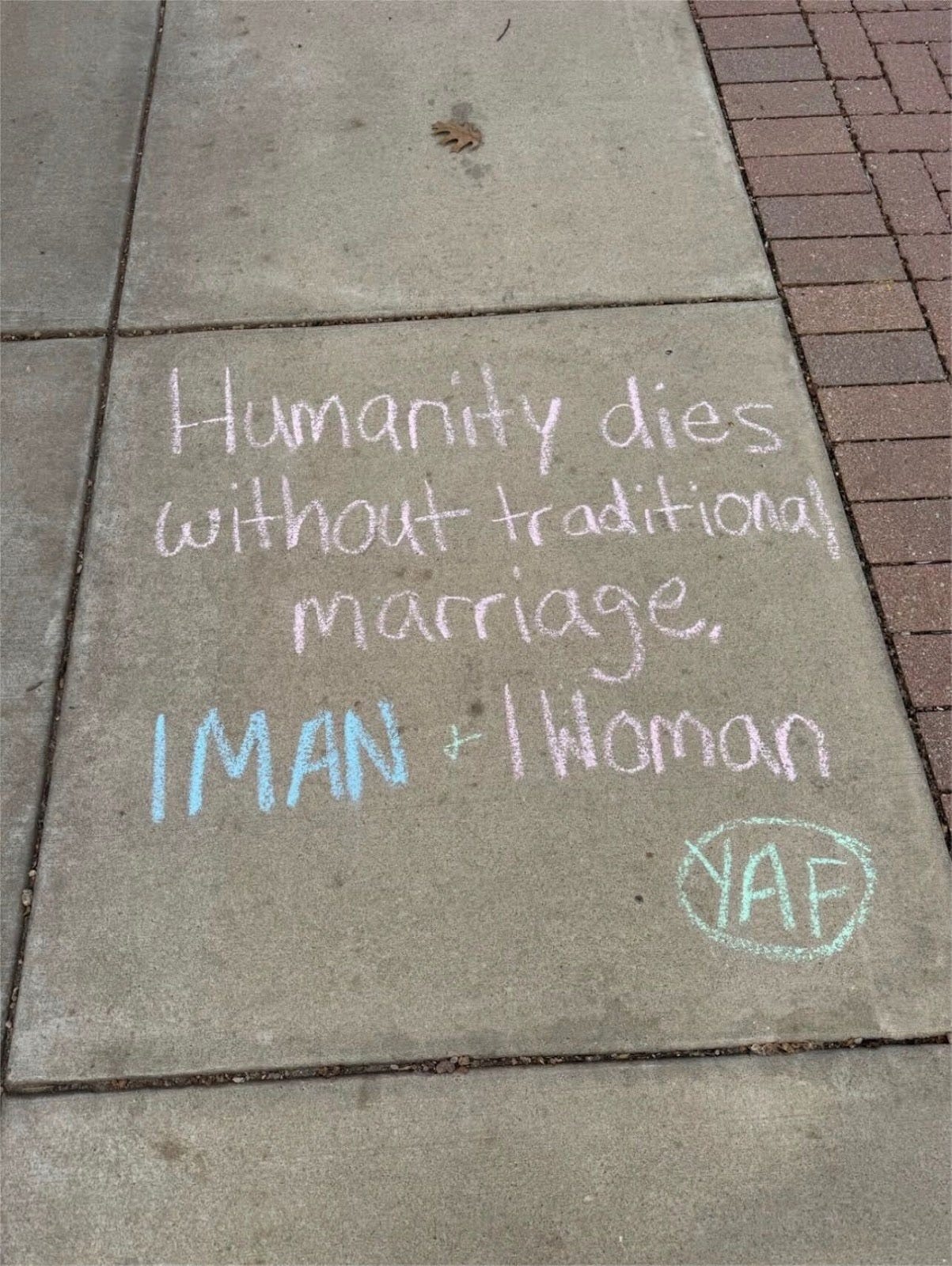

Like other right-wing campus groups, YAF has a reputation for provocative actions and rhetoric as well as for promoting anti-LGBTQ sentiments. Chapters have plastered campuses with chalk art denigrating gay marriage and hosted anti-trans speakers, including one who’s said that “transgenderism must be eradicated from public life.”

“Anti-LGBTQ groups on campus pose a unique threat to queer people because they’re in immediate proximity,” says Lauren Lassabe Shepherd, the author of “Resistance from the Right: Conservatives and the Campus Wars in Modern America.”

“They have access to their LGBTQ peers that off-campus agitators often cannot get. Anti-gay clubs are well-positioned to surveil, report on, and harass queer students, faculty, and other college employees where they spend the majority of their day either studying, working, and, in many cases, residing.”

What Is YAF?

YAF was founded in 1960 by conservative activist William F. Buckley Jr. It was one of the first campus-focused groups from a new wave of American conservatism pioneered by presidential candidate Barry Goldwater. The group garnered the support of future president Ronald Reagan and made its mark as an incubator for conservative politicians and activists. Noteworthy alumni include former U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions and former Vice President Dan Quayle, as well as the founders of right-wing groups including the Leadership Institute and Citizens United.

Shepherd says YAF began falling apart in the 1970s and showed little sign of life until 2011, when it was officially made a subsidiary of the similarly named Young America’s Foundation, another right-wing group that hosts youth-focused conferences and programs and was a member of Project 2025’s advisory board. Since then, it has increased in prominence, alongside its much more popular counterpart TPUSA, propelled by funding from right-wing megadonors including the Koch Brothers and Richard and Helen DeVos.

Shepherd says that YAF’s revival took place as conservative activists began to emulate Donald Trump during his rise in 2015: more provocative, more confrontational and, in some cases, more extremist. In 2017, The New York Times reported on the group hosting controversial speakers like Ann Coulter and Ben Shapiro. At the same time, YAF leaders would offer training to young activists, teaching them regulations on chalking, flyering and recording conversations. They’d also give them tips on how to pressure schools to cover security costs for speakers.

“The provocative ‘debate me bro’ or ‘prove me wrong’ is how groups with lesser profiles get noticed,” says Matthew Boedy, an English professor at the University of North Georgia and author of “The Seven Mountains Mandate,” a book published in September about Charlie Kirk and TPUSA. “But also, social media virality demands a provocation. And that is the goal.”

Shepherd also notes that the group’s higher-ups are not youth and have little connection to college campuses. Young America’s Foundation’s current president is 58-year-old former Wisconsin governor and Republican presidential candidate Scott Walker.

“That has a lot to do with older people who want to spread the word about conservatism … and of course they’re going to recruit on college campuses, because those are young people who are getting ready to begin their careers,” says Shepherd. “So yes, I have seen the resurgence, but no, I don’t think it’s organic.”

Sowing Chaos

Part of that resurgence is due to the spike in campus conservative activity after Kirk’s assassination. In the two weeks after his death, TPUSA reported over 121,000 new chapter requests.

“After I heard about the assassination of Charlie Kirk, I also was emboldened,” 20-year-old Kyle McBride told Uncloseted Media and GAY TIMES. “I’ve never been a joiner, but after that, it made me want to get involved.”

McBride, an engineering student at Rose State College in Oklahoma, says his school was home to one of those new TPUSA chapters. And since it launched at the start of the semester, he says it’s grown to become the second largest student group on campus, with 60 members.

Carrying that momentum, McBride is working to start a YAF chapter at his school. He says his main motivation for doing so is to boost his resume and to connect with like-minded people.

McBride says he believes gender transition is “morally wrong” and that “transgenderism, as a concept, should not be allocated across the United States,” but that trans people “must still be treated with full dignity” and “compassion.” Scholars and advocates have argued that there is no meaningful distinction between “transgenderism” and the existence of trans people.

While McBride and other right-wingers see this new wave of activity as an opportunity, Ted Pranikoff, a sophomore environmental design major at UB, feels endangered. He says that he got into an altercation with right-wing protestors on campus that ended in them grabbing and yanking at his wheelchair. Pranikoff also remembers YAF members and affiliates calling him and his friends “fags” and shouting, “Cripple repent and be healed.”

While McBride doesn’t agree with using slurs and insults because it “robs the person of their dignity,” he is also a proponent of free speech and doesn’t support “censorship,” even if it involves hateful rhetoric.

“You sort of just have to not condone it, but you kind of just have to let it go,” McBride says. “The only thing that’s really left to do is just say, ‘Hey, don’t do that.’”

Anti-LGBTQ Sentiment

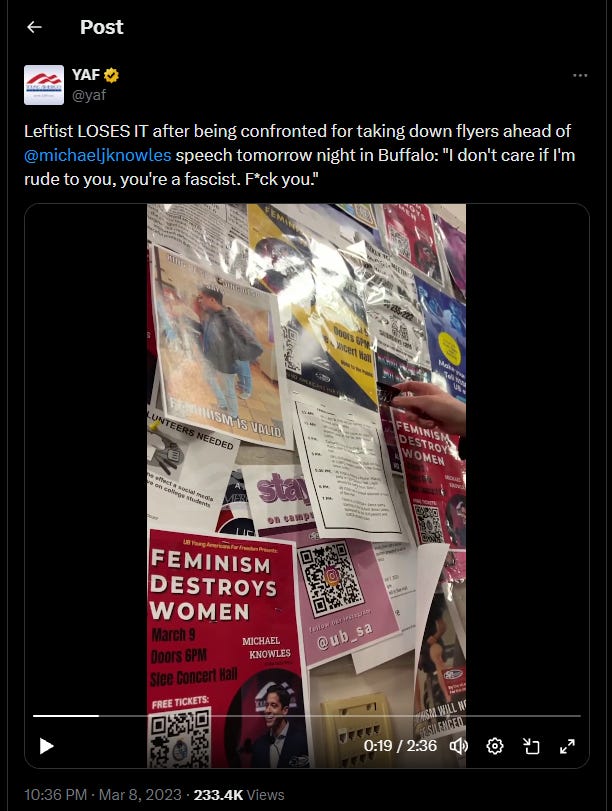

Still, many YAF chapters use inflammatory rhetoric to get a response from progressive students on campus, which they later post online to attract support from right-wing media.

The YAF chapter at Oklahoma State University has gotten backlash for discriminatory rhetoric, including chalk art opposing gay marriage with statements like, “Humanity dies without traditional marriage, 1 man + 1 woman.”

According to Jack Green, who graduated from UB in winter 2024, this behavior is not new.

“YAF made traps: They noticed some people were taking down their posters, so what they would do is that they would put up like 20 on one board, and then if somebody came and took it down, they would film them,” Green told Uncloseted Media and GAY TIMES. “I don’t really know what their goal was besides wanting to doxx people, to harass people.”

As YAF’s resurgence continues, so does its anti-LGBTQ footprint. University of Iowa’s YAF chapter has faced calls for suspension following leaked messages from a group chat that showed members using transphobic slurs in a conversation about other students on campus.

At the University of Alabama, all student groups are required to include a non-discrimination clause in their constitution. However, after complaining to the university on an email chain that also included the state’s attorney general, the YAF chapter was given an exception that allowed them to remove the terms “gender identity,” “gender expression” and “sexual identity” from their statement.

And at the University of Utah, YAF put up several posters claiming that “men shouldn’t be in women’s bathrooms” and “the transgender movement harms children.”

Extremism

Shepherd describes the typical YAF student as someone who “[is] in a fraternity, potentially an athlete, maybe on the debate team, [or] wears a suit to school.”

But in terms of political ideology, its members vary widely. McBride says his politics are more aligned with his interpretation of Catholicism than with modern conservatism. As a result, he differs from the majority of the group on some issues.

“I’m big into civil liberties, maintaining and preserving dignity for all people,” he says. “I’m not strictly against Trump, but a lot of the things he does and says I’m not really on board with. But it’s the closest group that I could find that champions at least some of my ideology.”

The group also includes a sizable population of more violent radicals. In 2007, the YAF chapter at Michigan State University briefly held the dubious distinction of being the only college student group to be designated as a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center, following an anti-LGBTQ protest that included slogans such as “straight power” and “end faggotry.” In 2022, that chapter’s former leader reappeared on campus, causing one student’s thesis presentation on YAF’s connection to white nationalism to be moved online due to security concerns.

Cassidy, the allegedly thwarted shooter, seems to have had more radical beliefs for quite some time. Cain Pietraszewski, a UB student who went to high school with Cassidy, says he was a “very stereotypical redneck Republican.”

“He was very open about his opinions,” they say. “A lot of anti-immigration, anti-non-white, non-straight, non-cis stuff. … It didn’t surprise me that someone of [Cassidy’s] mindset would make these threats.”

Shepherd says this form of extremism isn’t representative of YAF as a whole, “but they’re not an anomaly either. … It’s a strong contingency.”

Boedy says that contingency has grown because white nationalist influencer Nick Fuentes has pushed campus conservatism further to the right.

“There’s a different type of aggression or provocateurism that has come along in recent years, especially since Nick Fuentes came on the scene—he criticized and ambushed and did all different types of things to Turning Point to get it to be more racist,” Boedy says. “His followers will infiltrate these groups [and] become leaders. … He has influence on a lot of people who claim membership in Turning Point and YAF.”

At the same time, there are signs that anti-LGBTQ hate has been on the rise. In 2024, The Washington Post reported that annual hate crimes against LGBTQ people on both K-12 and college campuses had more than double the average for the latter half of the 2010s.

“It feels like [YAF] were almost restrained beforehand, and now they have permission to be mask-off, in-your-face racist,” says Pranikoff.

McBride says he’s not surprised to hear about this increase in extremism, but also says it wouldn’t dissuade him from starting his chapter.

“I was not intimately aware of YAF and its proclivity to produce or attract people like that, but I’m also not really surprised in general because this new alt-right pipeline is very potent,” he says. “If people come in and they’re interested in Catholicism, then I could probably easily dissuade them from a white supremacist or white nationalist kind of stance. But for people who are just with that view just because … I don’t know what I’d do with those people.”

Legal Threats

Despite YAF’s connection to radicalism, Green says the group is “coddled” by UB’s administration and often gets off with lighter treatment than other campus groups. He compares their reaction to YAF protests, which he says have rarely drawn the attention of campus police, with 2024’s pro-Palestinian encampment protests, where officers tackled and arrested protestors. More recently, campus police removed LGBTQ student activists from a sit-in protest at the end of the fall 2025 semester.

“Compared to us, it’s like night and day,” Green says. “YAF filming students without their consent, that didn’t cause them to have any [administrative] backlash at all. There also seems to be this weird support from the [campus police department] for YAF—whenever there’s a demonstration, you can always see a YAFer and a cop talking to each other and being friendly, while their relationship to basically everyone else is much more hostile.”

One reason may be that YAF chapters nationwide often respond to university backlash with legal threats. Last March, YAF’s Gettysburg College chapter filed a complaint with the Department of Education, accusing numerous diversity-related campus programs and LGBTQ student groups of “ongoing civil rights violations against conservative students.” And a legal threat convinced the University of Wisconsin-Madison to waive more than $4,000 in security and event fees for one of YAF’s events.

“Part of that can be explained by the fact that many YAF alumni are lawyers,” Shepherd says. “It’s a low-cost tactic because it’s in their professional wheelhouse. Lawsuits—or even just the threat of a suit—tend to scare colleges. They’d rather avoid a suit or settle than risk a headline.”

One of the first major actions Green remembers from YAF was inviting a correspondent for the right-wing media outlet The Daily Wire to speak on campus just days after an infamous speech where he said that “transgenderism must be eradicated from public life entirely.” In response, the school changed some of its policies regarding affiliations between campus and national organizations, leading YAF to lose its official organization status. The group then lawyered up with Southern Poverty Law Center-designated anti-LGBTQ hate group Alliance Defending Freedom and sued for first amendment violations and discrimination.

While the lawsuit, in which Cassidy was named as a plaintiff, was eventually dismissed, the policy YAF took issue with was repealed before it ever even went into effect.

“UB backed down immediately,” Green says. “They seem to be afraid of their lawyers, but also trying to have this weird middle ground, trying to be this very open queer-friendly university but also wanting to have this very conservative, homophobic … group on campus.”

What Can Universities Do?

Shepherd and Boedy both say that while Kirk’s killing has emboldened campus conservatives in the short term, it’s unclear if and how that will continue.

“Whatever momentum or inertia was behind Charlie Kirk as a man, there’s evidence to me that that has died off,” Shepherd says. “Now, ideologues and funders, those people are still invested in stirring the pot and poking the fire and keeping it alive.”

Shepherd says that universities should be more courageous in calling out hate among their students.

“We’ve seen how administrators have buckled under pressure from free speech absolutists on the right,” Shepherd says. “What administrators and media organizations that cover higher ed can do is recognize right-wing hate speech for the threat that it is, and be brave enough to protect the speech of their most marginalized students.”

Note: Uncloseted Media reached out to YAF as well as its chapters at University at Buffalo and Oklahoma State University. We also reached out to University at Buffalo’s TPUSA chapter, University at Buffalo admin, Nick Fuentes and Jacob Cassidy’s attorney for comment. None of these individuals or organizations responded.

If objective, nonpartisan, rigorous, LGBTQ-focused journalism is important to you, please consider making a tax-deductible donation through our fiscal sponsor, Resource Impact, by clicking this button: