Gay Boys and Sex Trafficking: An Under-Resourced Epidemic

Boys make up half of sex trafficking survivors, but there is only one safe house in the country that serves them.

Editor’s note: This story contains graphic depictions of sex trafficking, child abuse and sexual abuse.

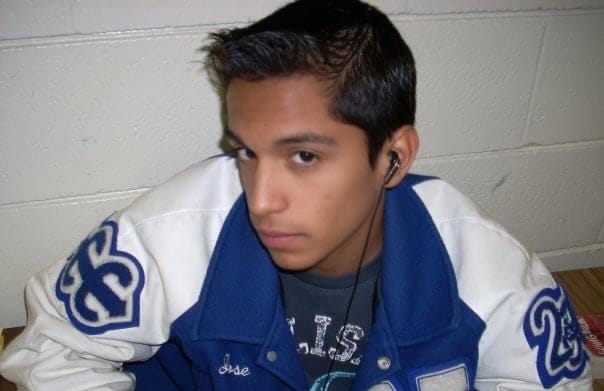

At 16 years old, Jose Alfaro remembers being trapped in a dimly lit room and told to give a naked stranger a massage and “let him do what he wants.”

“I was terrified and I had a bodily reaction of tremor, just shaking uncontrollably,” Alfaro, now 34, told Uncloseted Media. “I felt cold, even though I wasn't cold. I didn't know what to do when I'm in a room with two adult men and the door is locked.”

Alfaro, who was raised in the small, conservative town of Navasota, Texas, says he was given the choice of conversion therapy or living on the streets after he came out to his parents. In search of a male mentor, he leaned on relationships with older men he met online for acceptance and for basic needs, including a place to live.

He started messaging with Jason Gandy, a 31-year-old he met on Gay.com. Gandy began by asking Alfaro questions about his day and telling him he cared about him and wanted to be his friend.

“He showed a tremendous amount of sympathy and presented this world of luxury and wealth, and said that he wanted to support me and take care of me,” Alfaro says.

Alfaro, who was sleeping on a friend’s couch, “didn’t know where else to go,” so he began meeting with Gandy and subsequently moved into his place. Over time, Gandy exploited Alfaro to dozens of men for sex.

“Clients were allowed to do whatever they wanted to me,” he says. “I was uncomfortable, traumatized and at many times very, very violently hurt. I was terrified and in pain, but too afraid to leave. I didn’t know where I would go.”

It wasn’t until Alfaro was an adult and reflected on what happened that he realized he had been trafficked.

“The adults say this is normal, they're making me feel like this is okay,” he remembers thinking. “I was just trying to find ways to mentally accept it, especially without a way out.”

In 2018, a federal jury convicted Gandy on four counts of sex trafficking of minors, and he is currently serving a 30-year sentence.

While LGBTQ youth make up a disproportionate share of both homeless and trafficked populations, the experiences of queer boys are often unseen, dismissed or mislabeled. A 2023 report says that boys represent the “fastest-growing segment of identified human trafficking victims.”

While research is limited—especially due to underreporting—some reports say it is possible that almost half of sex trafficking survivors are boys. But as of 2025, there is only one safe house in the U.S. for men, and zero for boys under 18.

“Boys are less likely to come forward because of the stigma and because they don't think there's help available,” Bob Williams, the founder of that safe house, told Uncloseted Media. “People have no clue. People don't understand that boys are victims, too.”

Why Boys Are at Risk

Sex trafficking is the crime of using violence, fraud or coercion to force someone into commercial sex acts, often controlling their lives. According to Polaris, a leading anti-trafficking organization, LGBTQ people are seen as particularly vulnerable to being trafficked due to bias and discrimination and often a deeper desperation for a job or housing, which “gives traffickers an opening to step in and pretend to be the answer to a problem.”

While sex trafficking reportedly affects women more, these numbers likely don’t paint the full picture. Boys or men who are victims of sexual violence are less likely than girls or women to self-identify, partially due to societal messaging about being tough.

Jonathan Doucette, hotline training and development manager at Polaris, says that gay boys struggle with fitting into traditional masculinity and may feel even more shame.

“I was silenced by society long before I was silenced by my trafficker,” Alfaro says. “Society tells me something's wrong with me because I'm gay. Society tells me something is wrong with me because I am not masculine enough. And so therefore, I'm the problem and no one is going to help me.”

After Alfaro moved in with Gandy, he remembers being placed on a strict regimen of working out twice a day and eating only greens and healthy protein. Alfaro was allowed a phone upon request to “get his parents off his back” and earned the privilege to walk around the block alone.

Once Alfaro was in “good enough” shape, Gandy proposed that he start working at his massage business with him, which was a cover for sexually exploiting boys under 18.

Gandy would put up ads of Alfaro on his own website and taught him how to post on Craigslist to get clients and “earn money.” He told Alfaro that he would be in trouble if anyone found out because he was a minor.

After three months of being forced to have anal sex, be fondled and give oral sex to over 50 men, Alfaro escaped, leaving in the middle of the night while Gandy was asleep.

But where was he going to go?

Why Boys Are Overlooked

According to a 2013 report by Every Child Protected Against Trafficking, law enforcement has “little understanding” of commercially sexually exploited boys. For example, they believe boys are not pimped and therefore not in need of services.

“We're led to believe that men are perpetrators and women are victims,” says Steven Procopio, a clinical social worker who works with male survivors. “We don't have a national dialogue like women have. … There's a lot of gender bias when it comes to trafficking survivors and a great deal of homophobia. People are not looking out for it.”

Under the Trump administration, resources have been buried even further underground. Trump’s executive order that restricts federally funded websites from using language related to sex or gender forced Polaris to remove references to gender from parts of its website.

“It hasn't changed anything in how we meet survivors on the hotline or how we train people,” Doucette told Uncloseted Media. “But it makes people feel even less welcome. It is certainly not a good thing for queer boys looking for help. … They don’t see themselves listed [or represented].”

“I was so ashamed,” John-Michael Lander, an author and keynote speaker from Ohio, told Uncloseted Media. “I thought it was my fault, and I didn’t know how to come forward. … I would wear the same thing every day at school and not shower just to get someone to check on me [but] no one did.”

Lander was groomed and trafficked throughout high school. In a 2021 testimony, he says his mentors in the swim world, which included a doctor and a lawyer, reached out and built trust with his mother in an effort to control him.

“[The lawyer] would manage the money and pay the diving costs in alignment with the legalities to keep my amateur status. He indicated that he knew other professionals who wanted to help and provide the family with their expertise.”

These men were leading a trafficking circle, which led to Lander, at 14, being exploited into sex for the first time with a 60-year-old man at a motel.

“I had never had sex with anybody,” he says. “I was really scared. And I remember I froze, I couldn't move. And it was like I left my body.”

Every weekend for four years, Lander remembers being driven to Columbus, Ohio, and “auctioned” off with other young teenagers in white Speedos on stage while men walked around the room. They would be sold for the weekend and the men could do what they wanted.

Lander says the culture of sports and masculinity made it hard to talk about because people expected him to “be tough.”

“It seems hard for the public to understand how a coach or person in power could sexually abuse a male athlete,” Lander says. “Many men think that they can handle it and push the experience aside, and ‘get over it.’”

“There's toxic masculinity in our culture where if you do express vulnerable feelings as a boy when you're growing up, you’re … met with hostility or anger from people in your life,” says Doucette. “The stigma can just be so large that survivors might feel like [they] have to take care of this by themselves.”

“I felt so isolated,” says Lander. “When I finally told my mom what was happening, she looked at me and she slapped me across the face and said, ‘It's not nice to make lies about people. If this person or these people were doing this, you must have caused it.’”

So Lander stayed silent.

Why Boys Don’t Get Help

When boys muster the courage to come forward, they often don’t receive the resources they need.

Jesse Leon experienced this after he was trafficked from 11 to 14 by a shopkeeper who locked him in the backroom of a convenience store and sexually abused him. He eventually brought in other men who were allowed to drug Leon and do whatever they wanted sexually.

“Sometimes it'd be just somebody who wanted to do oral sex on me. Sometimes it would be more,” Leon told Uncloseted Media. “[The shop owner] threatened that if I didn't return … he would find out where I live and kill me and kill my family.”

He says that messaging about masculinity, especially coming from a Latino household, where machismo culture encourages boys to be tough and take care of their family at all costs, made him go back every day.

At 14, Leon was addicted to hard drugs and severely traumatized. After three years of being trafficked, he got into a bloody fight at school because he was “seeing the faces of all the men” who were abusing him. The school reported it, and the state sent him a therapist for weekly talk therapy. But he needed much more support.

“She never once recommended drug and alcohol treatment, even though she knew I was addicted,” he says. “No one from the state ever followed up. Once I was handed off, they assumed that because I was in therapy that I was getting the resources I needed. No one checked in with me and when my mom asked for a translator or a therapist who could speak Spanish, they said no.”

Leon says that he feels he was overlooked because he was a boy. “Males can't be victimized,” he says. “There's still a belief that males are perpetrators, they're not victims. There's no safe space for men to destigmatize reaching out for help. You deal with it, it happens, you move on.”

A 2023 report found significant gaps in recognizing and responding to trauma in boys who are experiencing or are at risk of sexual exploitation. While many indicators of trafficking are consistent across genders, boys often express trauma through externalizing behaviors such as aggression, defiance, anger or bullying—responses that are frequently misinterpreted by providers as delinquency or behavioral disorders like ADHD, rather than signs of victimization.

“Law enforcement just doesn’t realize that this is happening,” says Williams. “If we can't help these young boys, they face a lifetime of addiction, prison or death.”

Because male survivors often don’t self-identify due to stigma, homophobia and mistrust of authority, Williams says that professionals must be trained to recognize nonverbal cues and build trust over time. Effective training also requires confronting gender bias; challenging the myth that trafficking is only a women’s issue; and creating safe, affirming spaces for male victims to disclose.

Almost 20 years later, Alfaro is still recovering. He now works full time in advocacy, centering on spreading awareness on the domestic trafficking of minors and underscoring the importance of increasing resources for marginalized communities and—in particular—queer boys.

“I did not know what resources were,” he says. “I didn't really think that there was anything that could help me. … I don’t want anyone to feel like that ever again.”

If objective, nonpartisan, rigorous, LGBTQ-focused journalism is important to you, please consider making a tax-deductible donation through our fiscal sponsor, Resource Impact, by clicking this button:

This needs more attention, thank you for bringing up this topic.

i was trafficked as a boy, and when I started talking about it right around the time I transitioned, nobody cared - I also was later sexually assaulted post-transition, and nobody cared then either because I lived in a red state and I was a "man in a dress", to them.

this article hits home. I live every day with the weight of this and even supposed professionals don't give a damn about talking about the trafficking despite it being one of the single most formative traumatic events in my long life filled with many.

I am almost 40 and still crushed by what happened to me when I was 17.