'[He] Helped Me ... Hate Myself': Conversion Therapy Survivors Speak Out

As the Supreme Court appears poised to reverse Colorado’s conversion therapy ban, survivors of the discredited practice speak with Uncloseted Media.

Editor’s note: This article includes mention of suicide and self-harm. If you are having thoughts of suicide or are concerned that someone you know may be, resources are available here.

“You don’t feel secure in your masculinity,” Sam Nieves remembers his licensed therapist telling him at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah. “Go grab a Playboy and find a way to enjoy it,” the Mormon therapist told him.

“He told me I can’t be straight if I don’t go fishing with my dad,” says Nieves, who was 20 at the time. “He told me I needed to play more sports, listen to country music, stuff like that. He told me something was wrong with me.”

After these sessions, which lasted about a year and a half, Nieves started experiencing crippling shame and self-loathing. He eventually developed excruciating migraines and memory loss.

“My therapist just helped me find better ways to help me to hate myself,” Nieves, now 41 and living in Seattle, Washington, told Uncloseted Media.

What Nieves was experiencing was conversion therapy, the discredited practice that seeks to change one’s sexual orientation or gender identity. The American Psychological Association, the American Medical Association and other major mental-health organizations have long condemned the practice as pseudoscience and incredibly harmful.

Fourteen countries have a national conversion therapy ban, while many more have state or provincial bans. In the U.S., religious leaders can practice nationwide, though licensed therapists are not allowed to apply it to kids in 23 states.

While research around torture and mental health consistently suggests the practice should be banned, almost 700,000 LGBT adults have received conversion therapy at some point in their lives, including about 350,000 who received it as adolescents.

Despite all of this, on Oct. 7 the Supreme Court heard arguments in Chiles v. Salazar, a case that challenges Colorado’s conversion therapy ban and—if overturned—would have implications for the rest of the states with bans in place.

While the verdict will likely not be announced until June, the court seems poised to overturn it, suggesting that restrictions on therapists might violate the First Amendment’s free-speech clause.

“I’m emotionally devastated for the children who will lose the protections we fought so hard to give them,” says Nieves.

Conversion Therapy and Self-Hate

Unlike many young Americans who are forced into the practice by their parents, Nieves—who was raised Mormon—opted to see a conversion therapist because his church community said that if he didn’t change his sexuality, he was letting them down.

“I actively didn’t want to be attracted to guys,” he says. “And so it was always this confusing, gaslighting situation where they would tell me to stop being gay, even if I wasn’t doing anything. I was trying really hard not to. That’s when [the church] referred me to conversion therapy.”

Nieves’ therapist insisted that his mom was too overbearing and his dad was not actively parenting, causing him to be gay. As his therapist continued to recommend that he engage in stereotypically masculine activities, he began to withdraw, cutting off friendships and avoiding community gatherings. His Mormon upbringing had taught him to feel shame, but conversion therapy solidified it.

“Conversion therapy gave me validation for why I hate myself. It was just building on top of what the church had already taught me,” he says.

Links to Dissociative Identity Disorder

Nieves became depressed and eventually developed a mild type of dissociative identity disorder (DID), where he experienced one persona that carried shame and recognized he was gay, and another that tried to act straight. Headaches and mental fog were persistent. Thoughts of ending his life flickered through his mind.

“It was just nonstop, massive disassociation,” he says. “There was the Straight Sam and the Gay Sam. And the whole time, everyone was telling me Satan was working on me because something inside me was trying to be gay. So it was insane making. They were making me clinically insane.”

According to medical experts, repeated trauma like medical procedures, war, human trafficking, conversion therapy and terrorism can cause DID when it overwhelms a child’s ability to cope, causing their sense of self to fragment into distinct identity states as a survival mechanism. The trauma disrupts the normal integration of self, leading to symptoms like memory gaps, dissociation and distinct personality states.

When Hunter Moore, a 29-year-old queer woman now living in Washington, was subjected to conversion therapy from her church and parents, she developed DID.

Raised in rural Idaho and immersed in an Independent Fundamental Baptist church that condemned queerness as sinful, the constant fear and shame brought on by her church’s conversion therapy program fractured her sense of self. She attributes her condition to repeated trauma that caused her brain to wall off painful memories.

“I didn’t know how to handle it other than just to check out,” Moore told Uncloseted Media. “I still have a lot of memory gaps from the conversion therapy because of how intense it was. … Once I didn’t have the restraints of that church anymore, the memories started to return.”

Fear, Shame and Suicidal Ideation

Similar to Nieves and Moore, Addy Sakler, who grew up in a conservative Protestant community in Ohio, says conversion therapy was “slowly killing” her.

“I figured I liked girls in kindergarten but did not have the language to describe it,” she told Uncloseted Media.

Sakler knew she wouldn’t be accepted at her church, so she put herself in conversion therapy throughout her young adulthood.

But it didn’t work. Sakler remembers the first sneaking moments of affection between grad school classes with her first crush. But after each kiss, the joy was followed by shame.

“We’d feel a lot of guilt and break up and immediately go repent,” she says. Both women were part of a church ministry that promised to “pray away the gay,” a 12-week program of lessons and deliverance sessions meant to convert them to heterosexuality. Instead, Sakler says, it nearly destroyed her.

“I felt like a zombie walking around. I was depressed and I tried to commit suicide,” she says. “I was in the hospital for a month, two different times. It created a lot of trauma.”

Sakler says she was white knuckling it, trying to get through life as a “shell of a person.” She began cutting, hitting and hating herself because of the rejection from her church community.

“You believe what they’re saying. They’re telling you you’re broken and to be right with God you have to be heterosexual and if you’re not changing, then you’re being attacked by Satan.”

For nearly 15 years, Sakler attended conversion therapy conferences across the country, including one put on by the now dissolved Exodus International.

According to the Williams Institute, LGBTQ adults who have undergone conversion therapy have nearly twice the odds of attempting suicide and 92% greater odds of lifetime suicidal ideation compared to those who haven’t. Among LGBTQ youth, the numbers are higher, with 27% of those who experienced conversion therapy attempting suicide in the past year.

In addition, survivors experience disproportionately high rates of depression, PTSD and substance abuse. According to the findings from one Stanford Medicine study, the psychological harm caused by conversion therapy mirrors that of other severe traumas known to cause PTSD—like sexual or physical assault, the loss of someone close, or even experiences of war and torture.

Isolation and Families Torn Apart

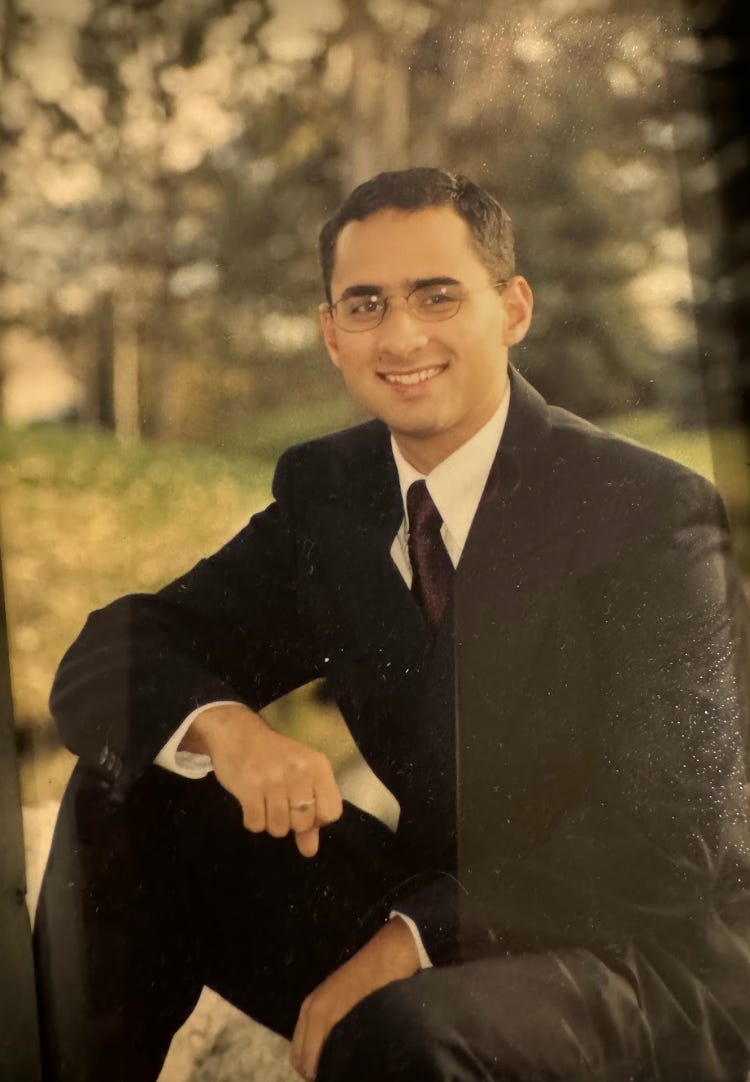

When Curtis Lopez-Galloway told his parents he was gay at 16, they drove him two hours away from his house in southern Illinois to a conversion therapist who used the sessions to berate him for not trying hard enough to change into “the man that God wanted” him to be.

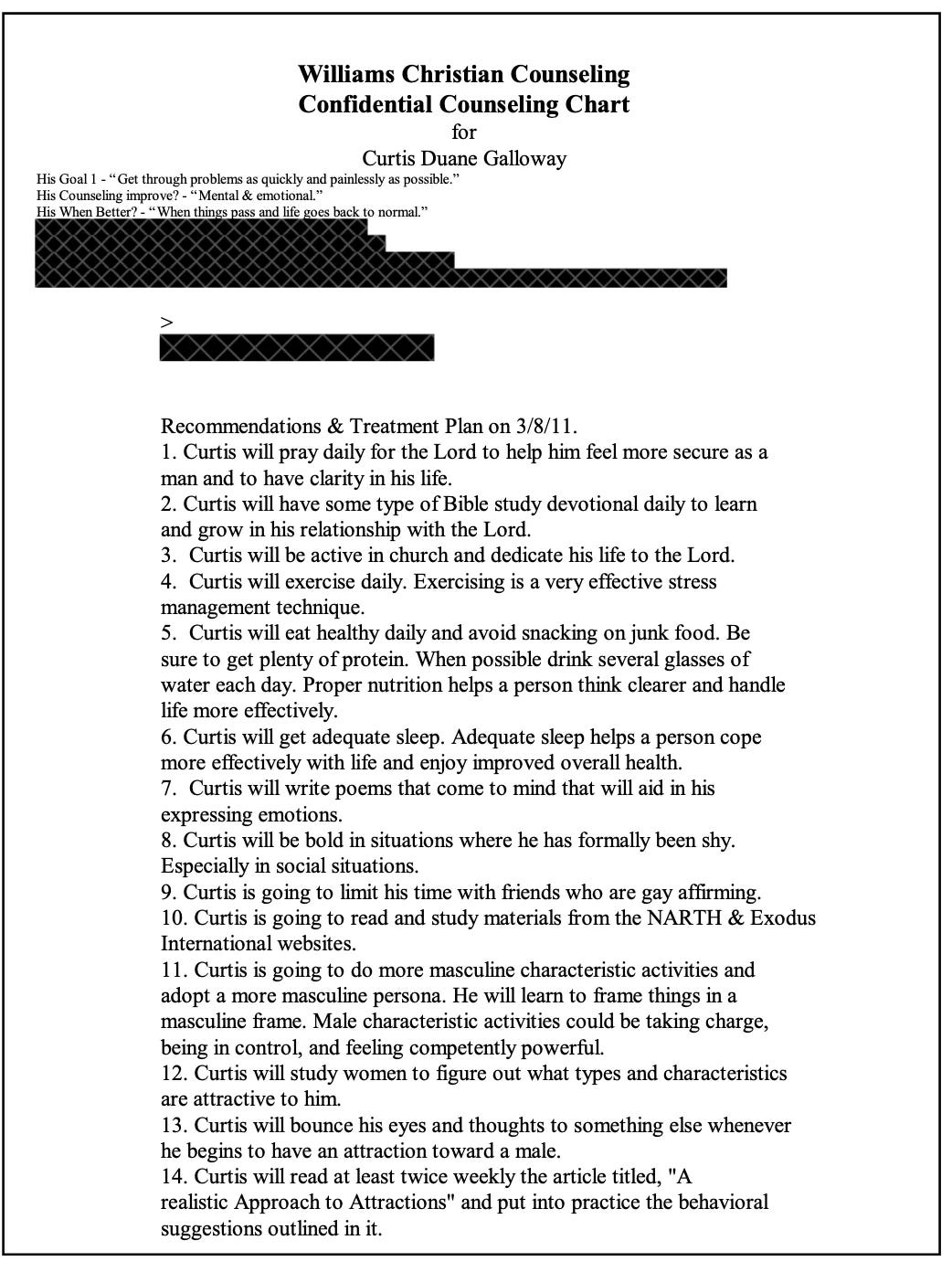

Lopez-Galloway remembers being told that his attractions to other men were a symptom of a deeper lack of masculinity, that he needed to “study women to understand what kind of man he was supposed to be” and that he should “bounce his eyes, and change his thoughts to something else whenever he begins to have an attraction toward a male.”

He was given a treatment plan that involved limiting time with LGBTQ affirming friends, reading articles designed to redirect his attractions, and practicing what the therapist called “male characteristic activities,” such as taking charge and asserting control. He told his therapist that his marker of when things would be better was “life [going] back to normal.”

The therapist also worked with his parents, telling them they had failed by allowing the “gay agenda” to threaten their family and “let the devil get into the house.”

Lopez-Galloway, who now runs the Conversion Therapy Survivor Network, a nonprofit that connects survivors of the practice, recalls frustration and shame spilling into screaming matches that tore his family apart. “My parents were miserable, I was miserable, and we would just take it out on each other,” he says. “I went to [my therapist] for six months, and he just abused me and made life worse. It pushed me deeper into the closet and made me anxious and depressed.”

“[My therapist] would use therapeutic ideas but twist them in a way that was trying to change sexuality. … He would try to manipulate me in that sort of way and really broke me down as a person,” says Lopez-Galloway.

We reached out to the center Lopez-Galloway went to for treatment but they did not respond to a request for comment. Lopez-Galloway says his parents now acknowledge the harm the therapy caused, and he says their relationship has improved.

Life After Conversion Therapy

For many survivors of conversion therapy, the trauma can last a lifetime.

Even 21 years later, Nieves still gets triggered. He dropped out of college during his last semester of counseling school because the practices were too similar to those manipulated and weaponized by his therapist. “The hardest part was fighting … to no longer be suicidal every single day,” he says. “I would say that’s the hardest part. … It’s the suicidality that you fight with once it’s over.”

Nieves and Moore have both found support in Lopez-Galloway’s survivor network, where they meet weekly and heal together in community. Sakler has found healing in therapy for PTSD, and has found acceptance with her wife and her queer community in Sacramento, California.

Despite this, the trauma often requires undoing self-hatred and discovering self-worth.

“[We’re] constantly saying, ‘We don’t know who we are,’” Nieves says. “We don’t know how to enjoy life. We don’t know what the meaning of life is. We’re like The Walking Dead. Because just like how you break a horse, they broke our spirits. They told us everything about us was wrong and we needed to conform. But no matter what we did, we couldn’t conform.”

Even with these survivors’ experiences, along with countless testimonies from other Americans over decades, the Supreme Court looks poised to overturn Colorado’s ban, with multiple justices describing it as “viewpoint discrimination.”

Nieves strongly disagrees and advises kids who are experiencing conversion therapy right now to stay strong and ask for help when possible. “This may very well be the most difficult time of your life. For many of you, it’s going to feel like a living hell, and you may even pray for death every night. I know this, because this is how [I] felt too,” he says. “Often, [conversion therapists] break other laws. If you think someone might be breaking the law during your conversion therapy, please seek out a trusted adult and let them know,” he says.

Above all, Nieves tells kids to push through no matter what. “It can and will get better if you promise yourself that you deserve authentic joy, free of lies and coercion. Community is out there waiting for you, if you can just hold on for one more day, one more hour, or even just for one more minute.”

If objective, nonpartisan, rigorous, LGBTQ-focused journalism is important to you, please consider making a tax-deductible donation through our fiscal sponsor, Resource Impact, by clicking this button:

Thank you for including my story! I’m sad and angry for all of us who experienced conversion therapy and all the monsters that came with it and that still haunt us today. F*ck SCOTUS!

The one common denominator appears to be religion. Conversion therapy should be outlawed the world over because all it does is bring pain. Don't feel shame people because if you do, they win. You are who you are and that if anybody can't accept you for that then to hell with them. Family and religion included. The time will come when the world will stop being this way but until then live life on your terms. If some don't like it then TOUGH! You are who you are!