I’ve Come Out to my Alaskan Military Dad Seven Times. He Still Hasn’t Met My Husband

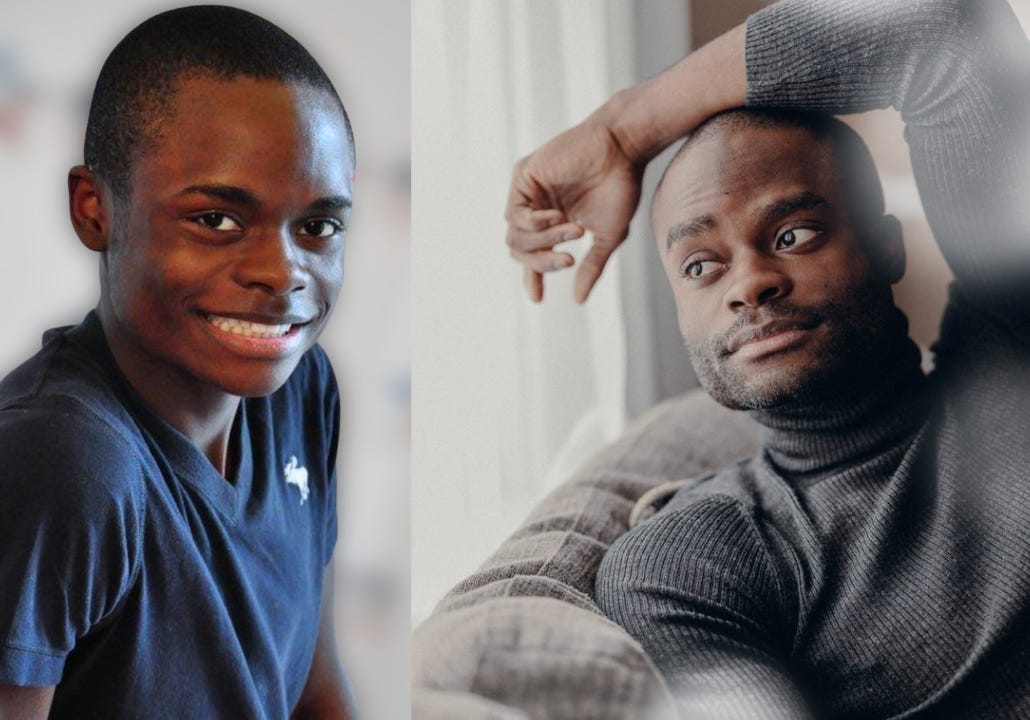

At 30, I’m finally living as myself. But the man whose acceptance I wanted most still can’t say the word gay.

Content warning: This story includes mentions of homophobia, childhood trauma and suicidal ideation.

By CorBen Williams

The seventh time I came out to my father wasn’t dramatic. It didn’t happen at a kitchen table or in a parking lot or after he’d found one of my journals. It happened casually, slipped into a conversation like it was nothing:

“As a gay man—” I began.

“You’re not gay,” he interrupted.

“Dad,” I replied. “We’ve done this too many times before.”

Even now, at 30 years old, married to the man I love, fully myself in ways I once thought impossible, my dad still can’t say who I am out loud. It hangs there, suspended between us, as though acknowledging my homosexuality would unravel something he’s built his entire life around.

I’m not sure what exactly. Control? Image? Masculinity? Maybe he simply doesn’t have the language.

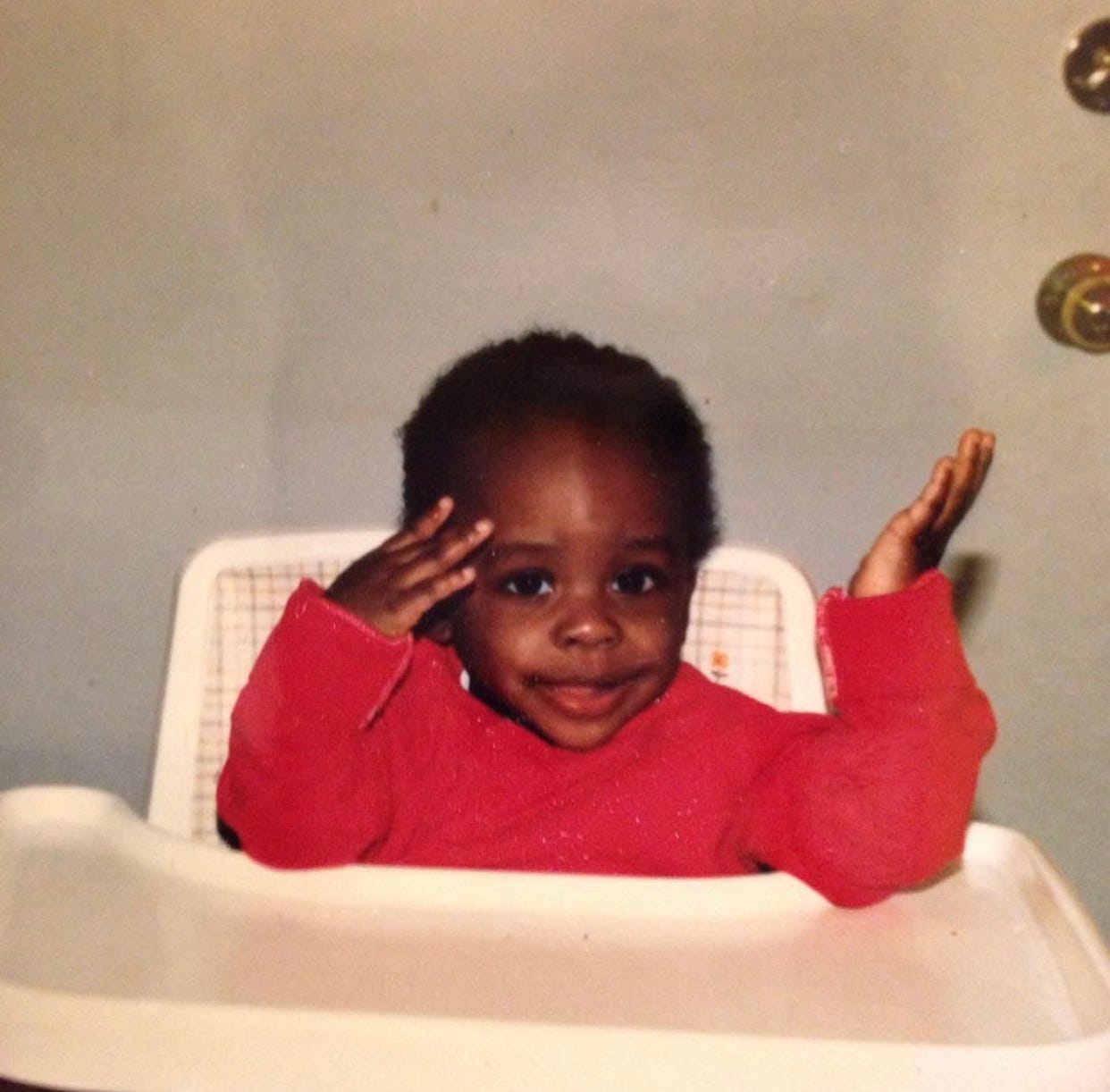

I grew up in North Pole, Alaska, in a red-sided house at the end of a gravel turnaround. It was the kind of home where the winter light never quite reached the living room and silence carried through the walls like a second language.

North Pole felt like its own universe. A 2,500 person military town where there’s snow on the ground for up to 187 days a year and the Christmas lights never come down. About 70% of the town is white and roughly 30% of the voters are registered Republican, with almost half listed as “undeclared,” which in Alaska is usually just Republican without saying it out loud.

Most families were tied to the church or the base, so you learned fast what was considered normal and what was not. People knew your parents and your business.

Growing up Black and queer made me stand out without trying and forced me to learn early how to tuck parts of myself away.

My parents had both served in the military, and even though my mother had the warmth and softness to move past it, my father emulated parental rejection. Dad demanded respect and expected excellence in the way a man shaped by the military does: loud and without room for negotiation.

You could feel his energy before you heard his footsteps because there was always a tension that entered the room with him. He yelled more than he spoke, and as a kid I was told to listen to what he was saying, not how he was saying it, even when he was screaming in my face.

My father didn’t know what to do with a son who felt things deeply, and before I ever came out to him—the first of seven times—he had already shown me exactly which parts of myself were unsafe to reveal.

But that didn’t stop me from trying. The first time I came out, I was in first grade, sitting in the parking lot of a McDonald’s on Geist Road, right beside my future high school.

“Dad, I think I’m bisexual,” I said.

I knew my ass was gay. But I also knew enough about my father to try to ease him into it. He asked if I knew what that meant, and even though I did, I told him “no.”

“It means you like sucking penis,” he spat harshly.

I was six.

People think kids don’t understand things, but children clock everything. That moment didn’t confuse me about who I was. It clarified who he was. It showed me that there were parts of me he couldn’t handle and wouldn’t protect. I didn’t leave that day understanding my sexuality better. I left understanding the risk of telling the truth.

The second time, I was forced out when my father found my journal. I was 10 years old, and in those pages, I’d written unpolished thoughts about men, about how I felt around them, questions I didn’t yet know how to ask anyone.

He burst into my bedroom and tore the journal up in front of me, little pieces of paper flying around me as I sat in my bed. I tried not to cry.

“As long as you’re a kid in my house, you don’t get privacy,” I remember him barking. It showed me that I need to be wary about how much I trust people and what information I give them.

This rejection led me to the darkest part of my childhood.

“I am tired of living,” I remember muttering to my sixth grade teacher.

I was exhausted by my dad, exhausted from hiding, exhausted from feeling wrong in my own skin.

I should have stopped writing after that, but writing was how I survived. When you don’t have anyone to talk to, you talk to the page.

By 13, I had another journal. This one had drawings of a classmate and fantasies about kissing him. When my dad found it, he brought it up on the car ride home from school, saying “the correct way” to feel about other boys was “brotherly love” and nothing else.

But the third journal set off the biggest explosion.

It was filled with details, drawings and fantasies about my first hookup with a boy. The way I wrote about them, at 15, was more adult. The kind of writing he didn’t want to believe his son was capable of.

“I fucking told you about this shit,” he shouted, with the journal gripped tightly in his hand. “This isn’t appropriate. This isn’t what we do.”

My mom was sitting next to me, shocked, both of us caught off guard by how quickly he had gone from discovery to explosion. I almost cried, but I swallowed it down. My mom guided him into the other room to calm him down.

He didn’t speak to me for seven days. He couldn’t look at me. Each day felt like another nail in the coffin.

I kept coming out to my dad anyway. At 17. At 22. At 24. Nothing changed.

Part of me used to think that I was an embarrassment to my family. I felt for so long that I needed to apologize for being the mistake. But in my late teens, I started to see it differently. I realized I just wanted his acceptance and his love in a way that I was never gonna get.

Because of this, I don’t think I ever really got to be a child. Even in first grade, when other kids were talking about Barbies and Legos, I felt like I was always bracing for impact, performing a version of boyhood that never fit. My childhood was spent preparing for adulthood and a career. People would always say to me, “You seem so much older. You seem so mature.”

I left North Pole for good and moved to New York City when I turned 19. I became a performer, a traveler, someone who learned to build softness and resilience, where my childhood had taught me to live in fight-or-flight mode. And then, almost when I wasn’t expecting it, I met Travis.

He was older. Wisconsin-born. A wildlife biologist. Patient in a way I didn’t even realize I needed. My mother said he softened me, brought grey into my black-and-white worldview. With him, I don’t brace for criticism. I don’t edit myself. I don’t shrink. I don’t hide my journals.

We’ve been together five years now, married for three. He’s met everyone in my life, except for my dad.

Now, when I think about my upbringing in North Pole, I think about the path through the woods that led to my house, hoping someone on the other side would understand me. I think about how many times I tried to hand my father my truth, and how many times he handed it back to me with rage.

Even now, with the life I’ve built and the love I’ve chosen, acceptance is still complicated. I wish I could say that learning to love myself erased the sting of not being understood, but the truth is I still wrestle with where I fit—inside my family, inside Black spaces, inside queer spaces, inside the places that were never built with someone like me.

I’ve learned to be confident, to be gracious, to be the person who makes others feel seen, maybe because I know exactly what it feels like not to be. But some days, even as a grown man, I feel an instinct to shrink.

I’m learning that acceptance is a practice, one I have to return to again and again. I don’t have it all figured out. But I’m trying. And maybe that’s the real truth at the end of all this: I haven’t just been coming out to my father all these years—I’ve been slowly, steadily learning how to come home to myself.

Uncloseted Media and GAY TIMES reached out to CorBen’s father for comment, but he did not respond.

Sam Donndelinger assisted with the writing and reporting in this story.

If objective, nonpartisan, rigorous, LGBTQ-focused journalism is important to you, please consider making a tax-deductible donation through our fiscal sponsor, Resource Impact, by clicking this button:

Yessssss CorBen.

I can totally relate. I could re-feel those rejections. My father would not talk about it. And I would not stop showing up wanting that acceptance. I am still trying to come to terms and he has been dead for several years now.

And thanks for reminding me to wait for that person who does not make me feel like I need to 'edit'. That's powerful.