Conversion Therapy Since 1886: A Dark History of the Discredited Practice

Even though conversion therapy is psychologically damaging, the Supreme Court appears poised to overturn Colorado’s ban on the practice.

This story was produced in partnership with @hankycodemagazine, an LGBTQ+ history publication.

Throughout history, the belief that homosexuality is a disease that needs treatment has been pervasive. During the Cold War, the moral panic from the “lavender scare” caused many folks to view homosexuals as national security risks. And many still believe that homosexuality is a threat to the nuclear family.

Since at least the 1800s, doctors and religious organizations have created various types of conversion therapy in an effort to cure LGBTQ people. But over time, the practice has become widely condemned by major medical organizations, 24 states have banned it for minors and a United Nations expert has said it “may amount to torture.”

Despite this, the Supreme Court appears set to overturn Colorado’s ban on conversion therapy in a case that was brought forth by Southern Poverty Law Center-designated anti-LGBTQ hate group Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF).

The history and development of conversion therapy is long and complex. To make sense of it, here’s a timeline of key events over the last 140 years.

1886

German psychiatrist Richard von Krafft-Ebing publishes “Psychopathia Sexualis,” a foundational sexology text that describes homosexuality as a psycho-neuropathic degenerative illness. Krafft-Ebing attempts to convert patients to heterosexuality through hypnosis. The practice marks an early foundation of what later becomes known as conversion therapy and reflects the medical community’s early efforts to find a cure for homosexuality.

According to the “Encyclopedia of Gender and Society,” Krafft-Ebing’s stance drastically changed by the end of his life:

“The experience of getting to personally know and work with such a great number of homosexual individuals made him change his initial views that same-sex desire was caused by hereditary degeneracy and accompanied by mental affliction and moral corruption. He came to the conclusion that most of his subjects were physically, mentally, and morally healthy, and that homosexuality was not the result of mental illness.”

1897

Magnus Hirschfeld, who was dubbed the “Einstein of Sex,” was unique in an era when people tried to cure LGBTQ people because he used science to argue against homophobia. In his 1902 “psychobiological questionnaire,” for example, he sought to provide data to show that homosexuals weren’t mentally ill. In 1897, he founded the Scientific Humanitarian Committee, the first LGBTQ rights organization, which had the motto: “Through science to justice.” Rather than trying to cure a patient’s homosexuality, he provided consultations to patients, often free of charge. Notably, Hirschfeld—who founded the Institute for Sexual Research in 1919—was the first documented physician in the world to provide hormone treatments and modern gender-affirming surgery to transgender folks. His work, however, would be tragically short lived when the Nazi’s destroyed the institute in 1933.

1899

German psychiatrist, physician and paranormal researcher Albert von Schrenck-Notzing claims he turned gay men straight through 45 sessions of hypnosis and trips to the brothel. Schrenck-Notzing’s theory stems from the now debunked idea that behavioral modification—such as forcing patients to engage in heterosexual activity with sex workers—could cure homosexuality.

1913

American psychiatrist Abraham Brill publishes “The Conception of Homosexuality” in the Journal of the American Medical Association. He writes:

“Of the abnormal sexual manifestations that one encounters none, perhaps, is so enigmatical and … so abhorrent as homosexuality. … I can well recall my first scientific encounter with the problem, ten years ago, when I met a homosexual who was a patient in the Central Islip State Hospital. Since then I have devoted a great deal of time to the study of this complicated phenomenon.”

Brill claims that “curing” homosexuality is possible, worth pursuing and that he’s achieved it multiple times. He distinguishes himself by practicing psychoanalysis and by criticizing physical “treatments” his peers experiment with, such as bladder washing, rectal massage and castration.

1918

Physiologist Eugen Steinach and surgeon Robert Lichtenstern—who both believe that homosexuality is caused by the testicles—begin work on the connections between hormones and homosexuality and publish “Conversion of Homosexuality through Exchange of Puberty Glands.” The article describes an experiment in which Lichtenstern replaces the testes of homosexual men with those of heterosexual men. After the transplant, they study the men’s sexual tendencies and conclude that heterosexual inclinations replace homosexual ones following surgery. However, the surgeon’s varying results lead medical professionals to doubt the validity of their findings.

1920

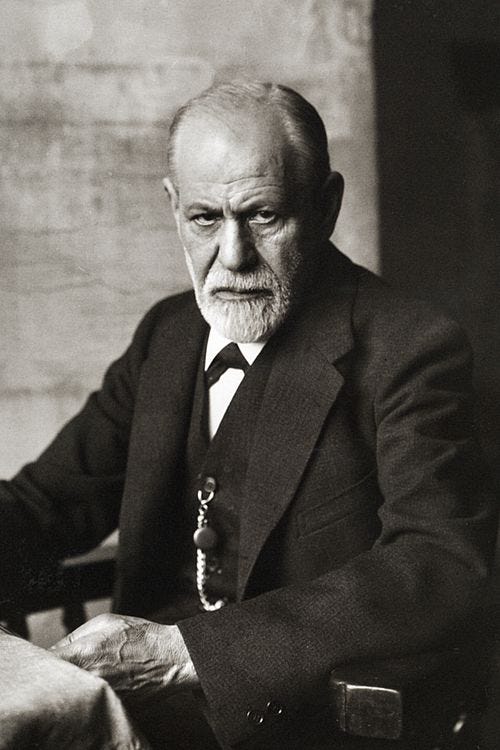

In “THE PSYCHOGENESIS OF A CASE OF FEMALE HOMOSEXUALITY,” Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, argues that homosexuality develops under specific conditions and describes conversion as unlikely. Unlike many of his predecessors, Freud does not see homosexuality as an illness or neurosis. He writes that “to convert a fully developed homosexual into a heterosexual does not offer much more prospect of success than the reverse.”

1930

Austrian physician and psychologist Wilhelm Stekel views homosexuality as a disease and publishes “Is Homosexuality Curable?” in The Psychoanalytic Review. Like Freud, he focuses on psychoanalysis and says that treatment works best when the patient wants it, writing:

“My experience during the past few years absolutely confirms my belief that homosexuality is a psychic disease and is curable by-psychic treatment. Tersely expressed: This disease in question is not a congenital condition but a psychic state which can be handled by treatment correctly applied.”

1952

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) defines homosexuality as a mental disorder in the first edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), a book that outlines recognized mental disorders and provides symptoms and evaluation criteria. The DSM classifies it as a “sociopathic personality disturbance.” This fuels a new era of psychiatrists and psychoanalysts who offer theories and cures, including talk therapy; aversion therapy, such as electric shocks or nausea-inducing drugs; hypnosis; and—in some cases—lobotomies.

1956

Psychoanalyst Edmund Bergler claims that if gay people want to change and receive the right therapeutic approach, they can be cured in 90% of cases. He uses confrontational therapy and frames punishment and shame as part of treatment, saying homosexuals suffer from “psychic masochism.” He publishes books with titles such as “Homosexuality: Disease or Way of Life” and “Counterfeit-Sex: Homosexuality, Impotence, Frigidity.”

In a 2025 paper in The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, the authors criticize Bergler’s findings, writing that:

“[He] pathologized homosexuality as a psychological illness and a moral failing, reinforcing the stigmatizing narratives about same-sex desire in mid-20th-century psychiatry. By sensationalizing his work through inflammatory language, Bergler positioned himself as a moral crusader, blurring the line between scientific inquiry and ideological condemnation.”

1973

After years of pressure from gay activists, the APA finally removes homosexuality from the DSM. The removal prompts many medical professionals to distance themselves from conversion therapy techniques. However, the DSM still contains “sexual orientation disturbance”—which would later be renamed “ego-dystonic homosexuality”—referencing individuals who are conflicted about their sexuality. For the next 14 years, this would serve as a backdoor to legitimizing conversion therapy as a valid practice.

A so-called “ex-gay” Christian ministry, Love in Action—also known as Restoration Path—is co-founded by Frank Worthen, who describes himself as a former homosexual.

One of their programs, Refuge, was a two-to-six week conversion therapy camp. Participants—mostly teenage boys—would spend their days engaging in acts such as “healing touch,” where the organization’s leaders would cradle and rock the boys in an effort to cure them.

In 2005, 16-year-old Zach Stark, who was a participant, wrote on his MySpace blog:

“Even if I do come out straight, I’ll be so mentally unstable and depressed it won’t

matter.”

1987

The APA removes “ego-dystonic homosexuality” from the DSM-III-R, with experts arguing:

“If there are no categories of mental disorders for short people who are unhappy with their height, eye colour or complexion, then why should there be one for distress related to sexual orientation?”

1991

American clinical psychologist Joseph Nicolosi publishes “Reparative Therapy of Male Homosexuality: A New Clinical Approach.” In the book, Nicolosi advocates for conversion therapy for “non-gay homosexuals,” or people who face conflict due to the societal stigmatization of their sexuality and—as a result—do not want to be gay.

1992

Alongside psychiatrists Charles Socarides and Benjamin Kaufman, Nicolosi launches the National Association for Research & Therapy of Homosexuality. The organization positions itself against mainstream medical views of sexuality and aims to “make effective psychological therapy available to all homosexual men and women who seek change.”

1998

Family Research Council, the American Family Association and 13 other far-right Christian groups spend $600,000 to promote the effectiveness of conversion therapy through full-page newspaper ads, including in The Washington Post and the Los Angeles Times. Family Research Council Director of Cultural Studies Robert Knight describes the ads as the “Normandy landing in the culture war.”

A few months later, the APA releases a position statement formally rebuking any “reparative” or “conversion” therapy designed to change a person’s sexuality. The position states that reparative therapy runs the risk of harming patients by causing depression, anxiety and self-destructive behavior. The APA joins the American Psychological Association, the American Association of Social Workers and the American Academy of Pediatrics in making a policy against reparative therapy.

2001

U.S. Surgeon General David Satcher issues a report stating that “there is no valid scientific evidence that sexual orientation can be changed.” That same year, American psychiatrist Robert Spitzer publishes a study that claims highly motivated homosexual people can become primarily heterosexual with the help of reparative therapy.

2009

The American Psychological Association adopts a resolution stating that patients should not be advised they can change their sexuality and that treatments predicated on homosexuality being an illness promote harm. Judith M. Glassgold, the chair of the task force, says:

“There is insufficient evidence to support the use of psychological interventions to change sexual orientation.”

2012

Exodus International, a major “ex-gay” faith-based ministry network that expanded into hundreds of local ministries since it was founded in 1976, publicly renounces conversion therapy. Their president, Alan Chambers, says, “We do not subscribe to therapies that make changing sexual orientation a main focus or goal.” Shortly after, Chambers would close the organization and apologize to participants for the “hurt” its programs caused.

That same year, Spitzer recants his study: “I owe the gay community an apology for my study making unproven claims of the efficacy of reparative therapy.”

2013

New Jersey becomes the first state to ban conversion therapy for minors by licensed psychologists, with the law receiving no pushback and immediately going into effect. This contrasts with California, which passed a ban in 2012 but received legal pushback and a preliminary injunction that delayed its enactment into law.

2018

Researchers at San Francisco State University find that attempted suicide rates among LGBTQ youth more than double when parents attempt to change their sexual orientation, and those rates increase further when therapists and religious authorities attempt conversion therapy.

2021

ADF, the Christian legal group that helped overturn Roe v. Wade, files a lawsuit on behalf of Brian Tingley, a licensed marriage and family counselor in Washington State. In the suit, ADF argues that the ban on conversion therapy practices hinders Tingley’s ability to treat patients despite the abundance of evidence showing how harmful said practices are.

The case is dismissed, appealed, dismissed again, denied to be reheard and finally declined to be heard by the Supreme Court in 2023. One judge states that health care providers should not be able to treat gay children by telling them that they are “the abomination [they] had heard about in Sunday school.”

2023

A letter titled “United States Joint Statement Against Conversion Efforts” is signed by 28 medical and psychological associations. It reads: “The purpose of the United States Joint Statement (USJS) is to protect the public by committing to end the practice of so-called conversion therapy in the US, which could have a spillover effect in other countries as well.”

2025

Twenty-seven states, D.C. and Puerto Rico have some form of protection for youth against conversion therapy. However, none of these protections apply to religious leaders.

The Supreme Court hears oral arguments in a case brought forward by Colorado mental health counselor Kaley Chiles, who argues that her state’s conversion therapy ban infringes on her freedom of speech. Chiles is represented by ADF. After hearing oral arguments in October 2025, the Supreme Court appears set to side with Chiles and the Christian legal group.

The court will rule on the case later this year. If they side with ADF, their decision could have implications for other states with conversion therapy bans and undermine care and rights for LGBTQ youth across the country—more than 40% of whom seriously considered suicide in 2023.

Additional reporting by Nico DiAlesandro.

If objective, nonpartisan, rigorous, LGBTQ-focused journalism is important to you, please consider making a tax-deductible donation through our fiscal sponsor, Resource Impact, by clicking this button:

Brilliant research. Excellent article and so important to have such important history set down accurately. Thank you.