Why Anti-Trans Hate Makes a Toxic Environment for Women Athletes

Earlier this year, 16-year-old AB Hernandez became the target of nationwide hate and harassment when the president of a local school board publicly doxxed the track and field athlete and outed her as transgender. Right-wing activists misgendered her and called her mom “evil;” swarms of adults showed up to heckle her at games; Charlie Kirk pushed state governor Gavin Newsom to condemn her; and President Donald Trump threatened to withhold federal funding from California over her participation.

While transgender athletes are very rare, this type of harassment towards them is playing out across the country and internationally. A trans girl was harassed at a soccer game in Bow, New Hampshire, by adult protestors wearing XX/XY armbands, representing an anti-trans sports clothing brand. And in British Columbia, a 9-year-old cis girl was accosted by a grown man who accused her of being trans and demanded that she prove her sex to him.

While research into the relative athletic capabilities of trans and cis women is ongoing, far-right groups, including the Alliance Defending Freedom and the Leadership Institute, have been putting hate before science to turn the public against trans athletes since at least 2014. And it’s working.

Laws, rules or regulations currently ban trans athletes from competing in sports consistent with their gender identity in 29 states, with 21 beginning the ban in kindergarten. The majority-conservative Supreme Court announced this month that it’ll be taking on the question of the constitutionality of the bans. Meanwhile, the federal government is pressuring states without bans to change their policies in compliance with a Trump executive order that attempts to institute a nationwide ban.

These bans have been successful in part because of a toxic and ruthless ecosystem of far-right influencers, like Riley Gaines, who have formed entire careers around attacking trans athletes by prioritizing hate and misinformation.

“So much of what we see … just seems like it’s wrapped up in really hateful and negative messages that aren’t good for anyone,” says Mary Fry, a professor of sport and exercise psychology at the University of Kansas. “We’re creating issues where maybe we don’t need to.”

Harassment and Mental Health

Grace McKenzie has been deeply affected by these hate campaigns. A lifelong athlete, McKenzie has stayed healthy by playing multiple sports where she’s met “amazing people.” Shortly after she transitioned in 2018, she was thrilled when she was invited to join a women’s rugby team at the afterparty of a Lesbians Who Tech conference.

“Rugby became my home, it was my first queer community, it was the space where I really discovered my own womanhood,” McKenzie told Uncloseted Media. “I could be the sometimes-masculine, soft-feminine person who play[s] rugby and loves sports.”

But that started to change in 2019, when McKenzie and others on her team started to hear rumors that World Rugby was considering a ban on trans athletes. Fearing the loss of her community, she started a petition that racked up 25,000 signatures—but it wasn’t enough, and the ban took effect in 2020.

As anti-trans rhetoric in sports has ramped up, McKenzie says she’s had soul-crushing breakdowns that have left her “sobbing uncontrollably and unconsolably.”

“It would be these waves of such intense despair and rage—it was like going through grief for five years,” she says. “I have to wake up every single day and read about another state or another group of people who say that they don’t want me to exist.”

While McKenzie says she’s found the strength to keep playing where she can, sports psychologist Erin Ayala has seen clients leave sports altogether due to the hate toward trans athletes.

“It can be really difficult when they feel like they’re doing everything right … and they still don’t belong,” says Ayala, the founder of the Minnesota-based Skadi Sport Psychology, a therapy clinic for competitive athletes. “Depression can be really high. They don’t have the strength to keep fighting to show up. And then that can further damage their mental health because they’re not getting the exercise and that sense of social support and community.”

That was the story of Andraya Yearwood, who made national headlines in high school when she and another trans girl placed first and second in Connecticut’s high school track competitions. The vitriol directed at her was intense: Parents circulated petitions to have her banned; crowds cheered for her disqualification; the anti-LGBTQ hate group Alliance Defending Freedom launched a lawsuit against the state for letting her play; and she faced a torrent of transphobic and racist harassment.

“It’s a very shitty experience,” Yearwood, now 23, told Uncloseted Media.

Fearing more harassment, she quit running in college.

“I understood that collegiate athletics is on a much larger and much more visible scale. … I just didn’t want to go through all that again for the next four years,” she says. “Track obviously meant a lot to me, and to have to let that go was difficult.”

It’s understandable that Yearwood and other trans athletes struggle when they have to ditch their favorite sport. A litany of research demonstrates that playing sports fosters camaraderie and teamwork and improves mental and physical health. Since trans people disproportionately struggle from poor mental health, social isolation and suicidality, these benefits can be especially crucial.

“In some of these cases, kids have been participating with a peer group for years, and then rules were made and all of a sudden they’re pulled away,” says Fry. “It’s a hard world to be a trans individual in, so it’d be easy to feel lonely and separated.”

Caught in the Crossfire

The anti-trans attacks in sports are also affecting cis women. Ayala, a competitive cyclist, remembers one race where she and her trans friend both made the podium. When photos of the event were posted on Facebook, people accused her of being trans, and she was added to a “list of males who have competed in female sports” maintained by Save Women’s Sports.

Ayala isn’t alone. Numerous cis female athletes have been “transvestigated,” or accused of being trans, including Serena Williams and Brittney Griner. During the 2024 Paris Olympics, Donald Trump and Elon Musk publicly accused Algerian boxer Imane Khelif of being trans after her gold medal win, as part of a wave of online hate against her. She would later file a cyberbullying complaint against Musk’s X.

While women of all races have been targeted, Black women have faced harsher scrutiny due to stereotypes that portray them as more masculine.

Yearwood remembers posts that would fixate on her muscle definition and compare her to LeBron James.

“I think that is attributed to the overall hyper-masculinization and de-feminization of Black women, and I know that’s a lot more prevalent for Black trans women,” she says. “It made it easier to come for us in the way that they did.”

A Big Distraction

Joanna Harper, a post-doctoral scholar at Oregon Health & Science University and one of the world’s leading researchers on the subject, says that the jury is still out on whether the differences in athletic performance between trans and cis women are significant enough to warrant policy changes.

“People want simple solutions, they want things to be black and white, they want good guys and bad guys,” Harper says, adding that the loudest voices against trans women’s participation do not actually care about what the science says.

“This idea that trans women are bigger than cis women, therefore it can’t be fair, is a very simple idea, and so it is definitely one that people who want to create trans people as villains have pushed.”

Even Harper herself has been the victim of the far-right's anti-trans attacks. Earlier this year, she was featured in a New York Times article where she discussed a study she was working on with funding from Nike into the effects of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) on adolescents’ athletic performance.

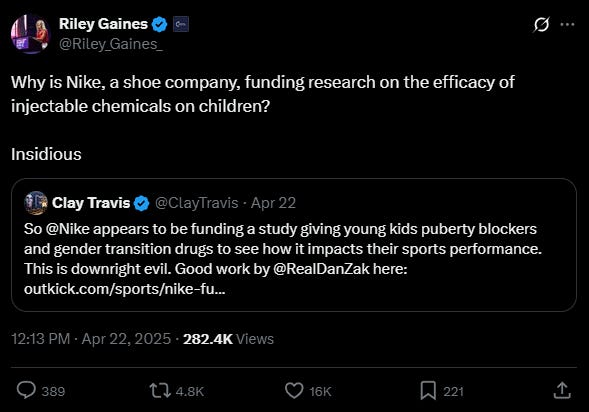

After the article came out, Riley Gaines, Turning Point USA and Fox News-affiliated sports outlet OutKick attacked Nike for funding the study.

“That Nike chose to fund a study on trans athletes doesn’t actually say that they’re supporting trans athletes. They’re merely supporting research looking into the capabilities of trans athletes,” Harper says. “You don’t know what the research will show until you get the data … but the haters don’t want any data coming out that doesn’t support what they want to say.”

Harper says this anti-trans fervor and HRT bans are making it more difficult to conduct studies in the first place.

And while the far-right argues that they are “protecting women’s sports” in their war on trans athletes, multiple athletes and experts told Uncloseted Media that this distracts from bigger issues in women’s sports, including sexual harassment by coaches and a lack of funding.

“If the real goal was to help women’s sports, they would try to increase funding [and] support for athletes,” says Harper, noting that women’s sports receive half as much money as men’s sports at the Division I collegiate level. “But that’s not what they’re doing, and it becomes pretty evident the real motivation behind these people.”

Moving Forward

Since Trump’s reelection, Grace McKenzie has somewhat resigned herself to the likelihood of attacks on trans people getting worse. Despite this, she finds hope in building community with other trans athletes, such as the New York City-based trans basketball league Basketdolls.

“If that's the legacy that [the anti-trans movement] wants to leave behind, good for them,” McKenzie says. “Our legacy is going to be one about hope, and collective solidarity, and mutual aid, and I would much rather be on that side of the fence.”

Meanwhile, Fry remains hopeful that conflicts can be resolved and that trans people may be able to find a place in sports over time.

“If we could all have more positive conversations and not create such a hateful environment around this issue, it would just benefit everyone.”

If objective, nonpartisan, rigorous, LGBTQ-focused journalism is important to you, please consider making a tax-deductible donation through our fiscal sponsor, Resource Impact, by clicking this button:

Anyone who is too good will be investigated and harassed.